Nov. 5 (UPI) — Human activity is destroying the world’s last wildernesses, and what’s left is concentrated in a handful of locations on Earth.

Researchers at the University of Queensland found that between 1993 and 2009, farming, mining and settlement wiped out a land mass of wilderness area larger than India.

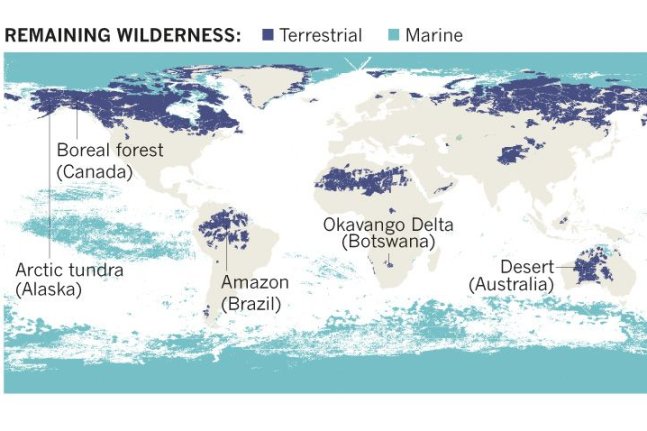

In fact, aside from a large tract crossing Africa, two-thirds of the remaining wilderness on Earth can be found in just five countries — Australia, Brazil, Canada, Russia and the United States.

“A century ago, only 15 per cent of the Earth’s surface was used by humans to grow crops and raise livestock,” James Watson, a professor at University of Queensland’s School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, said in a press release. “It might be hard to believe, but between 1993 and 2009, an area of terrestrial wilderness larger than India — a staggering 3.3 million square kilometers — was lost to human settlement, farming, mining and other pressures.”

Building on a 2016 project that charted existing terrestrial wilderness land, the study, published in the journal Nature, plotted ocean ecosystems, as well as the rest of the Earth.

“In the ocean, the only regions that are free of industrial fishing, pollution and shipping are almost completely confined to the polar regions,” Watson said.

The researchers found that more than 77 percent of land, excluding Antarctica, and about 87 percent of the ocean has undergone changes linked to human activity.

A total of 20 countries contain 94 percent of the world’s wilderness, with 70 percent held by just five countries.

“Some wilderness areas are protected under national legislation, but in most nations, these areas are not formally defined, mapped or protected,” Allen said. “There is nothing to hold nations, industry, society or communities to account for long-term conservation.”

Watson said stopping or slowing industrial development into wilderness areas and creating mechanisms for the private sector to protect wilderness areas, as well as expanding and improving the management of fisheries, could help.

“One obvious intervention these nations can prioritize is establishing protected areas in ways that would slow the impacts of industrial activity on the larger landscape or seascape,” Watson said. “We have lost so much already, so we must grasp this opportunity to secure the last remaining wilderness before it disappears forever.”